Gathering around to see what caretaker Greg Goin has for them are the “big dogs” in the herd of 60 Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation horses in his care.

In the one gas station town of Depew, Okla., across from the local mini mart, a spectacular example of horse-human communication blasts off like a rocket.

Sending up dust plumes in its wake, and leaving the uninitiated observer shaking his head with wonder, a herd of 60-plus Thoroughbreds, living the good life with the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation, spins, wheels and darts before galloping off as though summoned by the Mother Ship.

And in seconds they’re gone.

Thundering in unison across the 158-acre horsey Shangri-La of Rafter G Ranch, past beautiful ponds, and grassy fields, they meet up with the one man who can summon them with a powerful whistle.

Greg Goin, a former California contractor turned horse whisperer, says his transition from the construction business in the San Francisco Bay area to farming life in Oklahoma is like he “fell into a puddle of mud and came out smelling like a rose.”

In this week’s Clubhouse Q&A, Goin describes life with the 63 Thoroughbreds who follow him around like puppies.

Q: How did you go from city slicker to horse farmer?

Greg Goin surveys the 60+ Thoroughbreds he cares for as part of the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation’s Oklahoma herd.

I’d lived my entire life within the San Francisco area, and I knew I didn’t want to live out the rest of my life in the Bay Area, with the smog and the traffic. So I decided to try cattle ranching in Oklahoma, and moved out here in 2002 to this gorgeous ranch. People pay money to go on a vacation to a place that looks like this!

A year later, I met someone on the board of the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation, and that’s how it all began. We converted the farm from cattle to horses, and accepted our first Thoroughbred, Clever Song and his partner, a Morgan named Concord Bridge, in 2003.

Q: People say the herd treats you like another horse. What’s your secret?

I just have a knack with horses, I don’t know what it is. The first time I had a farrier come out, he called me a horse whisperer. But I said I was a greenhorn. But then I realized I could walk up to each horse and kiss everyone, and he couldn’t do that.

Q: And they come running when you whistle!

And they’re off! The herd comes running to the sound of Goin’s whistle.

I treat them like dogs. I didn’t train them; they learned. When I go out and feed, I can whistle really loud without putting my fingers in my mouth, which is important because I’m busy getting their feed ready. So when I’m out there and they hear me, they come running, and start circling around me. They’ve all learned to associate that whistle to getting fed, so now when I whistle for my dogs, they all come running!

Q: How do you single-handedly feed such a large herd?

Most of the time I have my tractor with me, and I’ll haul a four-by-four-by-eight foot hay bale. I put my tractor in reverse on its lowest gear, step out, and peel off a flake at a time. All the horses will gather and wait to dive in on their flake. We call it “controlled chaos.” They’ll kick and nip at each other, but they don’t come near me.

We have a system to meet the requirements of all the horses, from the older horse and the hard keepers on up to the easy keepers. In the summer, I’m pretty much done with my main feeding, except for some who I grain.

Greg says the 1,000-pound animals became his “big dogs” in a relationship that works so well.

I have about 13 who don’t keep as well, and come November, they get half again as much food as the main herd. And the older horses, or the ones with teeth problems, are in a pasture where we feed free-choice hay all the time. It never runs out. And then we have a few horses who come in during the winter. They’ll stay out grazing all day, but they come up to the barn because they know there’ll be a bucket waiting for them.

We float their teeth once a year, which is a four-day process, and we have their hooves trimmed four times a year. A farrier shows up with one or both of his sons at 8 a.m. and by noon, he’s done. I catch all the horses and hand them off to them, and it goes like clockwork. I guess you could say my main job is catching horses.

Q: Tell me about a special moment with your horses.

There’s one horse I have out there who we call Twiggy because she showed up here all skin and bones. When she arrived, she put her head down and ate, and she stayed like that for two years. She never came up to you, she was aloof and didn’t trust anyone. One day I’m out feeding and she came up and stood next to me. I pushed her away because I was putting out a huge bale of hay. After I was done, I went back up to her, and she lifted her hoof. She’d managed to get a rock stuck in her hoof. So I popped it out, and she actually brushed her head against my chest before she walked away.

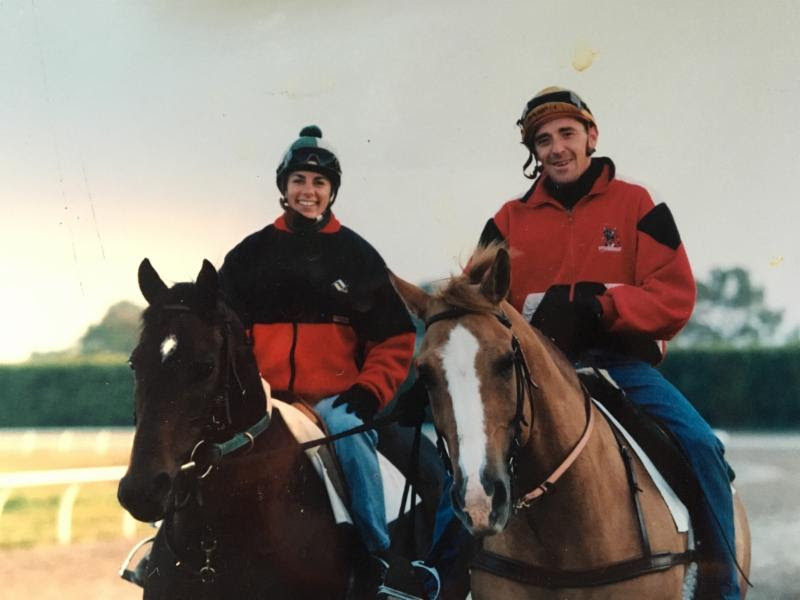

Goin’s daughters take after their horse whisperer father in their love of equines.

Another time I had a lame horse out near a pond and I couldn’t get him to move. I needed to get him back up to the barn so we could take care of him. I hit him on the rump, but he wouldn’t budge. Then another horse came up from the pasture, saw me hitting the horse on the butt, and started biting the lame horse’s butt to get him to move. This horse, French Rachell, bit that other horse all the way up to the barn. After that, I had a local boy’s club contact me looking for a horse. I told them about French Rachell and said he’d be wonderful. They were skeptical because he had a big front knee. But, after what he’d done for me with the lame horse, I knew he’d be great. And I also knew he’d be fine for children to ride. They took him into their program and became the star there. He gives rides to all the kids, and they love him.

Q: Why do you do this work?

It’s the relationships with the horses. I gotta admit, I love these big, silly animals. They come up to me, these 1,000-pound creatures, and they trust me. I’ve never hit a horse on this ranch. I try to make sure every experience they have is a pleasant one, and rather than hit, I feed them and reward them when they do something right. It’s just so cool.

It turns out that I’m pretty good at this. I guess I should stop calling myself a greenhorn.

— This blog is brought to you by the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation, the nations oldest and largest Thoroughbred charity. To learn more about the organization and its 900 horses, please visit http://www.trfinc.org.